As a BetterHelp affiliate, we receive compensation from BetterHelp if you purchase products or services through the links provided

Imagine for a moment that you are not a medical professional. You are just a regular person who has been feeling “off” for a few weeks. You go to the doctor, run some tests, and a few days later, you get a diagnosis.

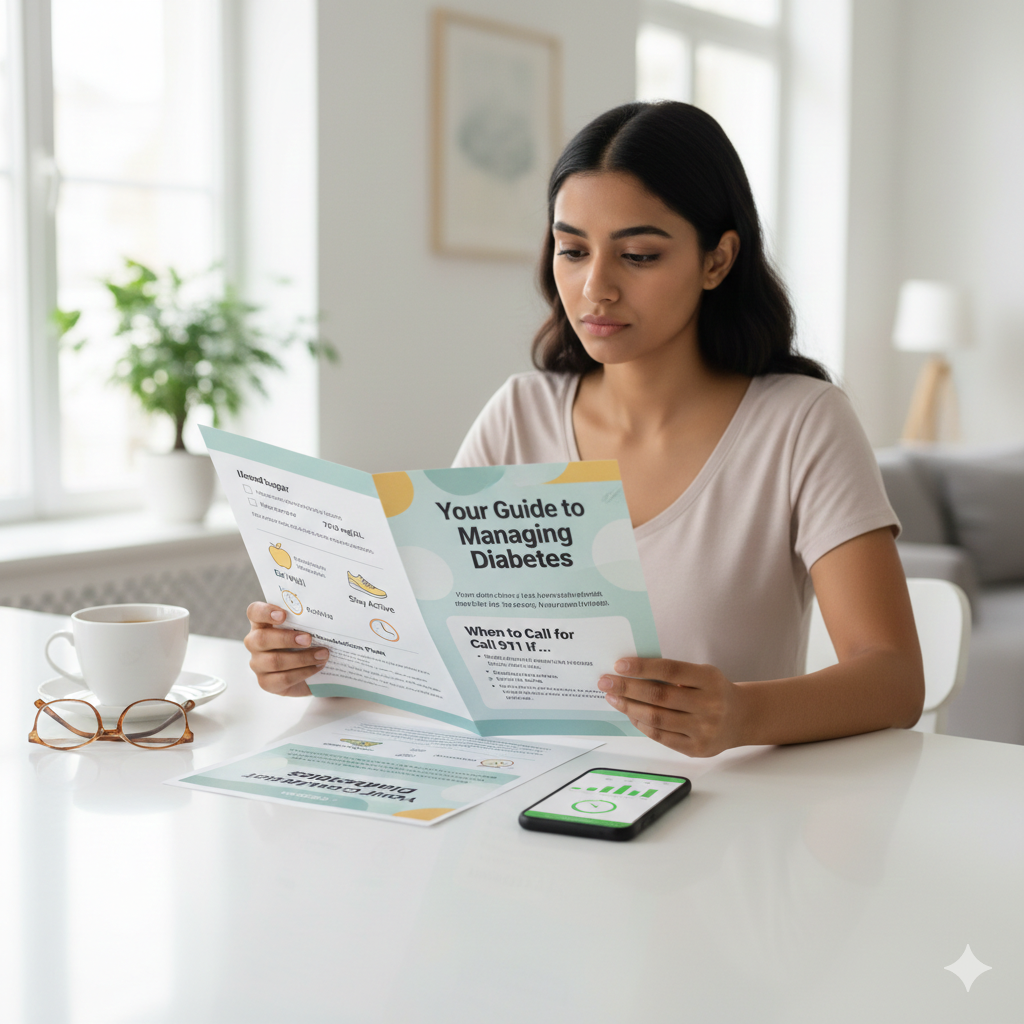

You are handed a packet of stapled papers or sent a link to a portal. You sit down at your kitchen table to read it, your heart rate already elevated. The first sentence contains the words “idiopathic,” “prognosis,” and “mortality rate.” What happens next isn’t education; it’s panic.

The gap between what doctors say and what patients hear is often massive. When medical information is dense, jargon-heavy, or poorly structured, it doesn’t just confuse patients—it scares them. Anxiety shuts down the brain’s ability to process information, leading to poor adherence to medication and missed follow-up appointments.

Creating materials that are medically accurate but emotionally accessible is a specialized skill. This is why many pharmaceutical companies and hospital systems partner with a specialized medical writing service to ensure their message lands safely. But whether you are outsourcing the work or drafting a brochure in-house, the goal remains the same: translate the science into safety.

Here are practical tips for writing patient information that informs without inducing a panic attack.

1. Ditch the Jargon

Medical professionals speak a dialect that they often forget is a foreign language to everyone else. Terms like “ambulatory,” “renal,” or “myocardial infarction” are precise, but to a patient, they sound cold and clinical.

The first rule of patient-centric writing is to write for the kitchen table, not the conference room.

- Don’t say: “Administer the analgesic agent via the oral route.”

- Do say: “Take this pain reliever by mouth.”

- Don’t say: “Hypertension.”

- Do say: “High blood pressure.”

This isn’t about “dumbing down” the science; it is about respecting the cognitive load of the reader. When someone is sick or worried, their reading comprehension drops. Aim for a 6th to 8th-grade reading level. Use tools like the Flesch-Kincaid readability test (built into Microsoft Word) to check your score. If you are hitting a college reading level, you need to simplify.

2. Design for the Skimmer

Nothing spikes anxiety faster than a solid wall of 10-point text. When a patient sees a dense block of paragraphs, their brain signals “this is hard,” and they likely won’t read it.

Your layout needs to be inviting. It should look like a guide, not a legal contract.

- Use Subheadings: Every new idea gets a bold header. “How to Take Your Medicine,” “Side Effects to Watch For,” “When to Call the Doctor.”

- Bullet Points are King: If you are listing symptoms or instructions, use bullets. They are scannable and digestible.

- White Space: Do not be afraid of empty space. Wide margins and spacing between paragraphs give the reader’s eyes a place to rest.

3. Frame Risk with Context

This is the trickiest part of medical writing. You have a legal and ethical obligation to list potential side effects and risks. However, reading a list of 50 terrible things that might happen (nausea, blindness, death) is terrifying.

Context is the antidote to fear. Don’t just list the risks; categorize them by likelihood.

- Group 1: “Common side effects (happens to 1 in 10 people).”

- Group 2: “Rare side effects (happens to 1 in 1,000 people).”

This helps the patient weigh the information. Instead of thinking, “This pill will make me go blind,” they understand, “Okay, I might get a headache, but the scary stuff is incredibly unlikely.”

Also, always pair a risk with an action. Don’t just say “May cause dizziness.” Say, “This medicine might make you dizzy, so stand up slowly and don’t drive until you know how it affects you.” Giving the patient agency reduces the fear.

4. Focus on Behavior Over Biology

Patients are generally less interested in the pathophysiology of their disease and more interested in how it changes their Tuesday morning.

Medical writers often spend too much time explaining why the disease happens (the biology) and not enough time explaining what the patient needs to do (the behavior).

Shift the balance. The biology section should be brief. The action plan should be the star of the show.

- Use active verbs: Take, Call, Rest, Eat, Avoid.

- Be specific: Instead of “Get plenty of rest,” say “Try to sleep at least 8 hours a night.”

- Be practical: Instead of “Avoid sodium,” say “Stop adding salt to your food and avoid canned soups.”

When a patient knows exactly what steps to take, they feel in control. Control reduces stress.

5. Validate the Emotion

It is okay to acknowledge that having a medical condition sucks. Clinical writing often strips out all humanity in an attempt to be objective, but a little empathy goes a long way.

You don’t need to be flowery, but you can be validating.

- “Starting a new medication can be stressful. Here is what you can expect in the first week.”

- “It is normal to feel tired after surgery. Give your body time to heal.”

These small sentences signal to the reader: “We know this is hard, and we see you.” It builds trust. When a patient feels understood, they are less likely to view the medical provider as an adversary and more likely to follow the treatment plan.

6. The “Teach-Back” Review

Before you publish or print your materials, put them to the test. Do not ask another doctor to read them; they already know the words.

Give the document to someone who has absolutely no medical training—your neighbor, your mom, or a friend who works in finance. Ask them to read it and then explain back to you what they are supposed to do.

- Did they understand when to take the pill?

- Did they know which side effect requires a 911 call?

- Did they look terrified while reading it?

If they are confused, your patient will be confused. If they are scared, your patient will be scared. Use this feedback to rewrite and refine until the tone is helpful, not alarming.

Information is treatment. The words you choose have the power to calm a patient’s nervous system or send it into overdrive.

By stripping away the jargon, designing for clarity, and focusing on actionable steps, you turn a scary diagnosis into a manageable plan. You aren’t just writing words on a page; you are handing someone a roadmap through one of the most difficult times of their life. Make sure it’s a map they can actually read.

- A Guide for Turning Your RV into a Sanctuary for Sleep - February 4, 2026

- High Stakes, Low Blood Pressure: How to Navigate the Chaos of Moving Hazardous Liquids - February 4, 2026

- The Driveway Mechanic’s Guide: How to Change Your Oil Without the Chaos - February 4, 2026

This site contains affiliate links to products. We will receive a commission for purchases made through these links.